It’s not about logic. It’s about loss. Here’s the psychological story of why we throw good money after bad—and how to finally stop.

Part 1: The Car at the Curb

The Opening Scene:

Let’s talk about Mark. Mark is a composite of friends, family members, and, if I’m being honest, a past version of myself. He’s standing on a cold, grey sidewalk, staring at his 15-year-old car. In his hand is a piece of paper from the mechanic’s shop, the estimate smudged with grease: $4,000 for a new transmission.1

A cold, rational calculation would be simple. The car itself is maybe worth $2,500, on a good day. Spending $4,000 on it is, by any objective measure, a terrible financial decision. Mark knows this.

But as he stands there, his mind isn’t doing that simple calculation. Instead, it’s playing a highlight reel of past pain. He’s thinking about the $1,500 he spent last year on new brakes and a full set of tires.1 He’s thinking about the $500 water pump six months before that.

This is the thought that springs into his head, clear as a bell: “If I give up now, I’ve wasted all that other money. I’ve already put so much into this…”.2

And just like that, the trap is set. He’s no longer making a $4,000 decision. He’s trying to redeem the $2,000 he already spent. He’s trying to justify his past choices. He finds himself convincing his wife, and himself, that this $4,000 will be the last repair. That this will “make it all worth it.”

He’s found himself in the “money-pit”.3 He’s trying to resurrect a “long-dead car”.4 And he is about to make a perfectly irrational, deeply human, and very bad financial decision.

We’ve all been there. Maybe for you, it wasn’t a car. Maybe it was a “dream” stock that has done nothing but plummet, an unused gym membership you pay for “just in case,” or a business idea that is draining your savings account dry. We stay in these bad situations, not because they make sense for our future, but because of the weight of our past.

This isn’t a story about a broken car. It’s a story about a bug in our human operating system.

Naming the Ghost in the Machine

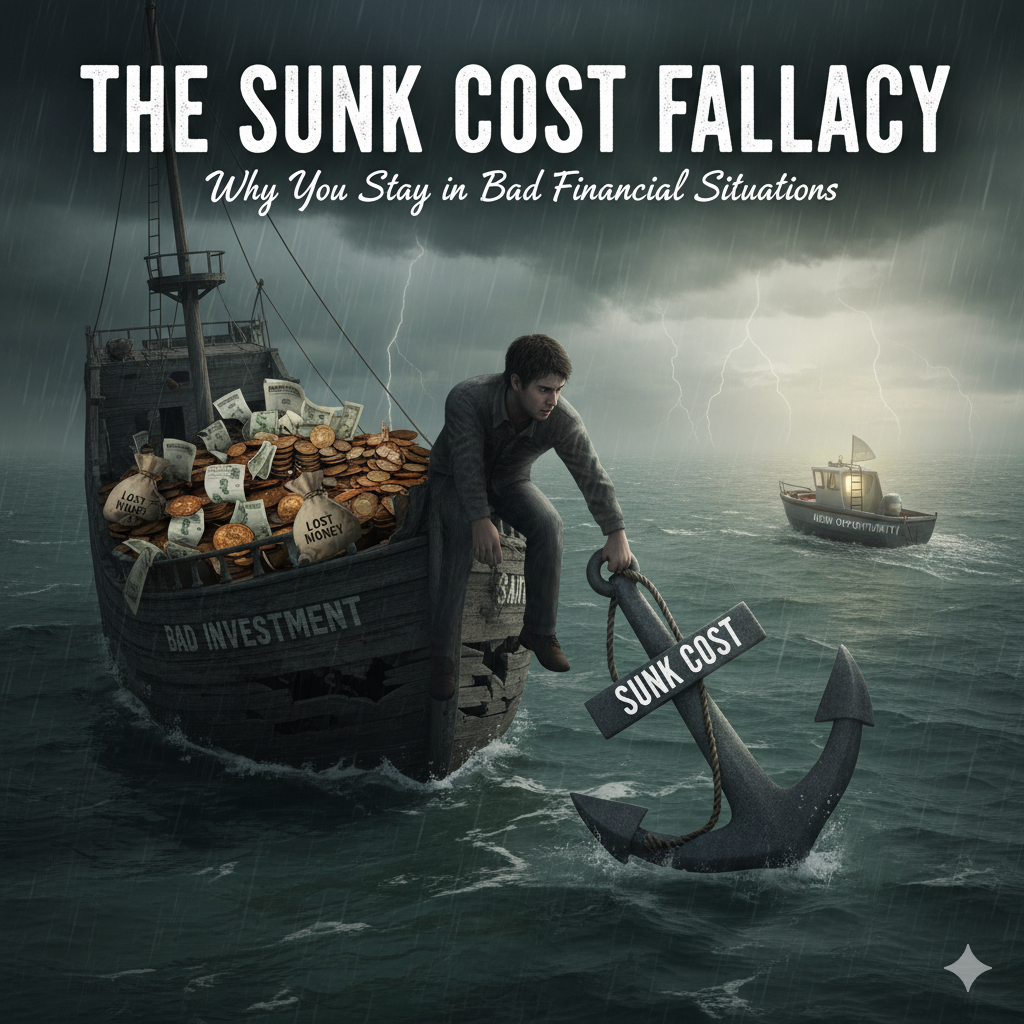

What Mark is feeling—that desperate, gut-pulling need to make a past investment “worth it”—is one of the most powerful and quiet thieves of our financial well-being. It has a name: The Sunk Cost Fallacy.

Let’s break that down, because a good definition is like a light in a dark room.

A “sunk cost” is any cost—money, time, or effort—that has already been spent and cannot be recovered.5 It’s gone. It’s “water under the bridge”.7 Mark’s $1,500 for the brakes and tires is sunk. He can never get it back, whether he fixes the car or sends it to the scrap yard.

The “fallacy” is the error in thinking. It’s the part where we let those irrecoverable, past costs influence our future decisions.7

The only rational question Mark should be asking is, “Is this car, in its current broken state, worth a new $4,000 investment to me?” The answer is clearly no.

But the Sunk Cost Fallacy makes him ask a different, loaded question: “If I don’t pay the $4,000, won’t I have wasted the $1,500 I already spent?”

This is the psychological trap that leads us, time and again, to do the one thing we all know we shouldn’t: throw good money after bad.4

Before you judge Mark, or yourself, you have to understand this: this isn’t a “stupid” mistake or a simple failure of logic. It’s a deep-seated, powerful, and emotional part of human psychology.8 It’s a cognitive bias, a glitch in our decision-making that affects everyone, from a person fixing a car to a CEO of a utility company refusing to terminate an economically unviable nuclear plant project.7

To understand how to fight it, we first have to understand why our brains are so fiercely committed to this losing strategy.

Part 2: The Psychological Conspiracy: Why It Hurts to Stop

We like to think of ourselves as rational beings, especially with money. We imagine a tiny CEO in our brain, sitting at a big desk with a spreadsheet, making logical choices. But the truth is, most of our financial decisions aren’t made by the CEO. They’re hijacked by the building’s high-strung, emotional Security Guard, who is obsessed with one and only one thing: avoiding a threat.

And the biggest threat? Loss.

The Ringleader: Loss Aversion

The mastermind behind the sunk cost fallacy is a concept from behavioral economics called Loss Aversion.

Here’s the simple, Nobel Prize-winning discovery: our brains are not wired to treat gains and losses equally. In fact, psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky proved that the psychological pain of a loss is about twice as powerful as the pleasure of an equivalent gain.11

Think about it. Finding a $100 bill on the street feels good.8 Losing a $100 bill you had in your pocket feels horrible.8 The two emotions aren’t even in the same league. We are fundamentally wired to avoid losses more than we are to seek gains.15

Here is the critical link: When Mark is standing on that sidewalk, his two options are not “fix car” or “don’t fix car.” In his brain, the options are:

- Option A (The Rational Choice): Scrap the car. But to his brain, this means admitting a $1,500 loss. It’s forcing himself to look at the $1,500 he spent and officially label it a “loss.” This is a certain loss, and it triggers that intense, twice-as-powerful psychological pain.14

- Option B (The Fallacy): Pay the $4,000. This, his brain argues, is an uncertain loss. Maybe this will be the last repair. Maybe the car will run for five more years and make the entire investment (the $1,500 + the $4,000) worth it.8 Maybe he can avoid the loss.

His brain, with its powerful, hardwired loss aversion, hates Option A so much that it tricks him into choosing Option B, even though the rational evidence screams it’s a terrible bet.8 We’d rather gamble on a high-risk, high-cost future than accept the certain, concrete, and emotionally painful loss in the present. We stick with the poor investment because we don’t want to feel bad about losing.8

The Accomplices: A Rogues’ Gallery of Biases

Loss Aversion is the ringleader, but it doesn’t act alone. It employs a whole crew of other biases to build the perfect psychological prison. These biases work together, stacking on top of each other to amplify the effect, building a powerful justification for the emotional pain we’re trying to avoid.

1. The Publicist (Commitment Bias)

This is our deep-seated desire to “save face” and appear consistent.18 We don’t want to admit we were wrong, especially if we made our decision publicly. What would Mark’s spouse say? What would his friends say? He told them this was a good, reliable car. Quitting now makes him look inconsistent, foolish, and like he “failed.” This is also called “escalation of commitment”—the tendency to be consistent with what we’ve already done or said, just to save face.18

2. The Inner Parent (Aversion to Waste)

This is that nagging voice in your head, the one that sounds suspiciously like a frugal parent, that says, “Don’t waste!”.8 In one study, “not wanting to be wasteful” was the most common reason participants gave for falling for the fallacy.16 This is why we’ll sit through all two-and-a-half boring hours of a movie we paid $15 for.8 This is why we’ll overeat a meal we already paid for, even to the point of feeling sick.21 We irrationally mistake the act of quitting (which is logical) for the act of wasting (which is emotional).

3. The Storyteller (Narrative Framing)

This is the most subtle and, perhaps, the most powerful. We are narrative creatures.23 We need our lives to make sense, so we frame our decisions as a story.

Abandoning the car means Mark’s story is: “I am a person who failed. I am a person who wasted $1,500”.20

Continuing the project, however, allows him to frame it as an overall success: “I am a person who saved this car. I am a fighter, not a quitter”.8 We will pay an enormous financial price—literally $4,000—to be the hero in our own story.

4. The Cheerleader (Optimism Bias)

Finally, there’s the voice of unrealistic optimism. It’s the voice that whispers, “It’ll pan out… just a little more…”.8 We’re wired to overestimate our chances of winning and underestimate our chances of losing, and this tendency gets stronger after we’ve already invested. The very act of investing thousands in a business makes you more likely to believe it will pan out, regardless of the actual evidence.8

Part 3: The Fallacy in the Wild: More Financial Stories

This “conspiracy” of biases doesn’t just live in mechanic’s shops. It’s at the heart of some of our worst and most common financial mistakes.

The “Break-Even” Investor

Let’s meet Sarah. Sarah bought a hot tech stock for $100 a share. It was the “next big thing.” It’s now trading at $40.

She’s a smart person. She reads the financial news. She knows the company’s outlook is terrible.25 Her financial advisor has told her to sell, take the tax loss, and move the money to a promising new opportunity.

What does she do? She holds.

Why? Because she has one, all-consuming, singular thought: “I’ll sell it when it gets back to even.”.25

This is the Sunk Cost Fallacy in a tuxedo. The $100 “break-even” price is an anchor, a number from the past that has zero relevance to the stock’s future.25 For a rational investor, the reference point is the current price ($40). The only question that matters is, “Will this $40 stock go up or down from here?”

But Sarah’s reference point has been psychologically shifted to $100.27 Every price below that—$90, $60, $40—feels like “the loss domain.” And as we just learned from Loss Aversion, to avoid the certain pain of selling and “locking in” that $60-per-share loss, she is willing to take the uncertain gamble of holding a failing stock 16, all in the hopes of one day getting “back to even.”

This trap is especially sticky with money. Research shows the fallacy is strongest with monetary investments, more so than with investments of time or effort.16 Why? Because time and effort are obviously gone forever. You can’t get last year back. But money… money feels recoverable.28 Holding the stock feels like a chance to get the money back, while selling guarantees the loss. This makes the financial version of the trap uniquely powerful.

The Doomed Project

This fallacy isn’t just for individuals; it’s a primary way that businesses fail.

Imagine a small business owner who spent $10,000 on a new marketing campaign. After six months, the data is crystal clear: it’s not working. The campaign has brought in only 10% of the expected signups, and the money spent is far more than the revenue gained.8

The rational move is to pull the plug immediately, “cut their losses” 5, and reallocate the remaining budget to something that is working.

But the owner’s monologue sounds familiar: “We’ve already invested so much, we can’t just stop now. We have to make it work. Let’s double the ad spend for next quarter”.9

This is a perfect example of Escalation of Commitment.18 They are now “insisting on more spending to justify the initial investment”.18 This creates a vicious cycle 20 where the costs are not just monetary, but also non-monetary: the owner’s time, their team’s effort, and their ego.5 Abandoning the project means “admitting that the initial investment was a mistake” 20, and that is often a psychological price that is too high to pay… until there’s no money left at all.

Part 4: Rewriting Your Financial Story: How to Escape the Trap

So, we’re all wired to fall into this trap. What do we do? How do we escape?

You cannot change your brain’s wiring, but you can change the questions you ask and the “mental models” you use. You can build a toolkit for rational decision-making.

The Antidote: From Past to Future

The core principle for escaping the trap is this: You must consciously and deliberately shift your focus.

Stop looking backward at what you’ve spent. That money is gone. It is a sunk cost.

Start looking forward at what you could gain.25

The financial term for this is Opportunity Cost.30 It’s a simple, life-changing concept: the “cost” of any decision is also the opportunity you give up by making it.

Every “yes” to the failing project is a “no” to a new, promising project. The $4,000 Mark is about to spend on his transmission isn’t just $4,000; it’s $4,000 he can’t use as a down payment on a reliable new car. That is the real, future-facing cost of his decision.

A Practical Toolkit for Rational Decisions

When you feel the emotional pull of the fallacy—that sick feeling in your stomach, that “I’ve come this far” monologue—run these mental scripts.

1. The “Revolving Doors” Test (The Outsider’s Perspective)

This is my favorite mental model, and it’s incredibly effective.32

Imagine you quit your job today. The next morning, you are re-hired as a brand-new consultant, with no emotional attachment to any past projects. Your only job is to look at the cold, hard facts and make the best decision for the company’s future.32

Now, apply this to your life. Imagine you are a total stranger, new to the situation.

- Would this new, clear-eyed you buy this failing stock today, at its current price of $40? (No.)

- Would this new you choose to acquire this 15-year-old car today for a one-time entry fee of $4,000? (Absolutely not.)

This mental trick works by creating instant emotional detachment.30 It allows you to “see the forest for the trees” 32 and make a decision based on facts, not history.

2. The “Advise a Friend” Test (The Compassion-Logic Flip)

We are, for some reason, far more rational and logical for our friends than we are for ourselves. When you’re trapped, use this to your advantage.

Ask yourself, “What would I tell my best friend to do in this exact situation?”.8

Think about it. If your friend “Mark” called you and laid out the car-repair story, you wouldn’t hesitate. You’d say, “Are you crazy? Ditch the car! That thing is a money pit!” You’d say it instantly, with 100% certainty. This simple question bypasses your own ego, your “fear of appearing wasteful” 8, and your “desire to save face” 18 and taps directly into your rational, compassionate core.

3. The “Pre-Mortem” (Setting Exit Criteria)

This is a preventative strategy for your next big investment.20 Before you put one dollar into a new project, stock, or business idea, you must define “failure” and “success” from the outset.8

Ask yourself, “At what point will I know this isn’t working?” Write it down. Be specific.

- “If this stock drops below $80, I will sell. No questions asked.”

- “If this new marketing campaign doesn’t produce 50 new clients in 3 months, I will pull the plug and try a new strategy.”

This pre-commits your rational, present-day self, and it sets a tripwire that your emotional, future self can’t ignore. It’s a contract you make with yourself to protect you from your own worst instincts.20

The “Ask This, Not That” Framework

The easiest way to change your thinking is to change the questions you ask. The Sunk Cost Fallacy feeds on loaded questions. You need to replace them with rational ones.

| The Situation | The Fallacy Question (What we do ask) | The Rational Question (What we should ask) |

| The “Money Pit” Car | “But I’ve already put $1,500 into it. Won’t that be a waste if I stop now?” 1 | “If I were a stranger, would I buy this car today for the $4,000 repair cost?” 32 |

| The Losing Stock | “How can I get back to my ‘break-even’ price?” 25 | “Ignoring my purchase price, is this stock a good investment at its current price?” 25 |

| The Failing Project | “We’ve come this far; we can’t quit now. How do we justify the costs so far?” 18 | “What would I advise a friend to do in this situation?” 8 |

| Any Decision | “How do I avoid ‘losing’ what I’ve already put in?” 8 | “What is the opportunity cost? What better thing could I do with this new money/time?” 30 |

The Final Reframe: It’s Not a Loss, It’s a Price

Here is the most important reframe of all. The money you spent on the bad stock, the failing business, or the long-dead car is not “wasted” if you learn from it.30

Think back to Mark. That $1,500 he spent on brakes and tires? That wasn’t a “loss.” It was the price he paid for an education. It was the tuition for the life-changing lesson: “How to Recognize and Defeat the Sunk Cost Fallacy.”

The money is gone.7 That’s a fact. But the lesson is yours forever. And that knowledge, which will allow you to make better, smarter, more rational decisions for the rest of your life, is worth far more than the money you “lost.”

You are not walking away with nothing. You are walking away smarter. And that is the final, and most powerful, way to rewrite your financial story.

Works cited

- Sunk cost: Don’t ‘throw good money after bad’ — bobsullivan.net, accessed November 15, 2025, https://bobsullivan.net/gotchas/everyday-economics/cognitive-bias/sunk-cost-dont-throw-good-money-after-bad/

- Your Fear of Loss Impacts Your Finances – The Physician Philosopher, accessed November 15, 2025, https://thephysicianphilosopher.com/loss-aversion/

- The Sunk Cost Fallacy – The Story : r/exjw – Reddit, accessed November 15, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/exjw/comments/o56b1x/the_sunk_cost_fallacy_the_story/

- Option not Obligation: How to Beat the Sunk Cost Fallacy | Nat Eliason, accessed November 15, 2025, https://www.nateliason.com/blog/option-not-obligation

- Sunk Cost Fallacy | Definition + Examples – Wall Street Prep, accessed November 15, 2025, https://www.wallstreetprep.com/knowledge/sunk-cost-fallacy/

- The Sunk Cost Fallacy in Decision-Making: Psychological Mechanisms and Implications in Finance, Business, and Daily Life, accessed November 15, 2025, https://tesi.luiss.it/41510/1/265431_CAPRINO_CHIARA.pdf

- Sunk cost – Wikipedia, accessed November 15, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sunk_cost

- How Sunk Cost Fallacy Influences Our Decisions [2025] • Asana, accessed November 15, 2025, https://asana.com/resources/sunk-cost-fallacy

- Explaining Sunk Cost Fallacy and How To Avoid It (2024) – Shopify, accessed November 15, 2025, https://www.shopify.com/blog/sunk-cost-fallacy

- Dream car ruled “dangerously inadequate” after $400k restoration : r/CarsAustralia – Reddit, accessed November 15, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/CarsAustralia/comments/11udgel/dream_car_ruled_dangerously_inadequate_after_400k/

- accessed November 15, 2025, https://thedecisionlab.com/biases/loss-aversion#:~:text=Loss%20aversion%20is%20a%20cognitive%20bias%20that%20explains%20why%20individuals,losses%20in%20whatever%20way%20possible.

- Loss aversion – BehavioralEconomics.com | The BE Hub, accessed November 15, 2025, https://www.behavioraleconomics.com/resources/mini-encyclopedia-of-be/loss-aversion/

- Loss aversion – Wikipedia, accessed November 15, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Loss_aversion

- What is the Sunk Cost Fallacy and How Does It Work? | Charles …, accessed November 15, 2025, https://www.schwab.com/learn/story/dont-look-back-how-to-avoid-sunk-cost-fallacy

- Loss Aversion – Everything You Need to Know – InsideBE, accessed November 15, 2025, https://insidebe.com/articles/loss-aversion/

- Loss Aversion and Perspective Taking in the Sunk-Cost Fallacy – BYU ScholarsArchive, accessed November 15, 2025, https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=6833&context=etd

- The Sunk Cost Trap: Why We Throw Good Money After Bad | Psychology Today, accessed November 15, 2025, https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/decisions-and-the-brain/202506/the-sunk-cost-trap-why-we-throw-good-money-after-bad

- What Is the Sunk Cost Fallacy? | Definition & Examples – Scribbr, accessed November 15, 2025, https://www.scribbr.com/fallacies/sunk-cost-fallacy/

- Loss Aversion and Perspective Taking in the Sunk-Cost Fallacy – BYU ScholarsArchive, accessed November 15, 2025, https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/5834/

- The Sunk Cost Fallacy – The Decision Lab, accessed November 15, 2025, https://thedecisionlab.com/biases/the-sunk-cost-fallacy

- How to Stop Sunk Costs Fallacy from Draining Your Finances? – Vrid Blog, accessed November 15, 2025, https://blog.vrid.in/2025/04/01/how-to-stop-sunk-costs-fallacy-from-draining-your-finances/

- Sunk cost fallacy – BehavioralEconomics.com | The BE Hub, accessed November 15, 2025, https://www.behavioraleconomics.com/resources/mini-encyclopedia-of-be/sunk-cost-fallacy/

- Economics and the Human Instinct for Storytelling | Chicago Booth Review, accessed November 15, 2025, https://www.chicagobooth.edu/review/economics-and-human-instinct-storytelling

- Narrative Psychology and the Art of Crafting Your Own Life Story | by Edward Reid | Medium, accessed November 15, 2025, https://medium.com/@edwardoreid/narrative-psychology-and-the-art-of-crafting-your-own-life-story-6fc1355b0023

- Let It Go – The Sunk Cost Fallacy and Smarter Spending | Uillinois, accessed November 15, 2025, https://blogs.uofi.uillinois.edu/view/7550/2103256839

- AG 093: Sunk Cost Bias & Loss Aversion – After Gambling, accessed November 15, 2025, https://www.aftergambling.com/ag-093-sunk-cost-bias-loss-aversion/

- Why choose wisely if you have already paid? Sunk costs elicit stochastic dominance violations, accessed November 15, 2025, https://www.sas.upenn.edu/~baron/journal/16/161220/jdm161220.html

- Loss Aversion as a Potential Factor in the Sunk-Cost Fallacy – PMC – NIH, accessed November 15, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7318389/

- What Were They Thinking? Reducing Sunk-Cost Bias in a Life-Span Sample – NIH, accessed November 15, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5125514/

- Sunk Cost Dilemma: What It Means, How It Works, and Example, accessed November 15, 2025, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/s/sunk-cost-dilemma.asp

- Mental Models for Projects — Tradeoffs | by Sumudu Siriwardana | Medium, accessed November 15, 2025, https://medium.com/@sumudusiriwardana/mental-models-for-projects-part-2-a7a4c6196cf3

- Beat the Sunk Coast Fallacy: Knowing when to quit – ikario, accessed November 15, 2025, https://ikario.com/sunk-cost-fallacy/

- Escaping the Sunk Cost Trap: When to Cut Your Losses in Legal Cases – Filevine, accessed November 15, 2025, https://www.filevine.com/blog/escaping-the-sunk-cost-trap-when-to-cut-your-losses-in-legal-cases/