Part I: The Awakening at the Register

The Shirt and the Stare

The fluorescent lights of the department store hummed with a quiet, hypnotic energy, casting a sterile glow over rows of neatly folded fabric. Leo stood in the center of the menswear section, his fingers brushing against the crisp cotton of a navy-blue button-down shirt. It was stylish, professional, and perfect for the upcoming office party. He flipped the price tag over: $60.

In Leo’s mind, the calculation was automatic and swift, a habit drilled into him by years of consumer training. He checked his mental ledger. He had $1,200 in his checking account. The credit card in his wallet had a $5,000 limit. Sixty dollars was a drop in the bucket. It was barely five percent of his bank balance. He could tap his card, walk out, and barely notice the transaction. The shirt was affordable. It was cheap, even.

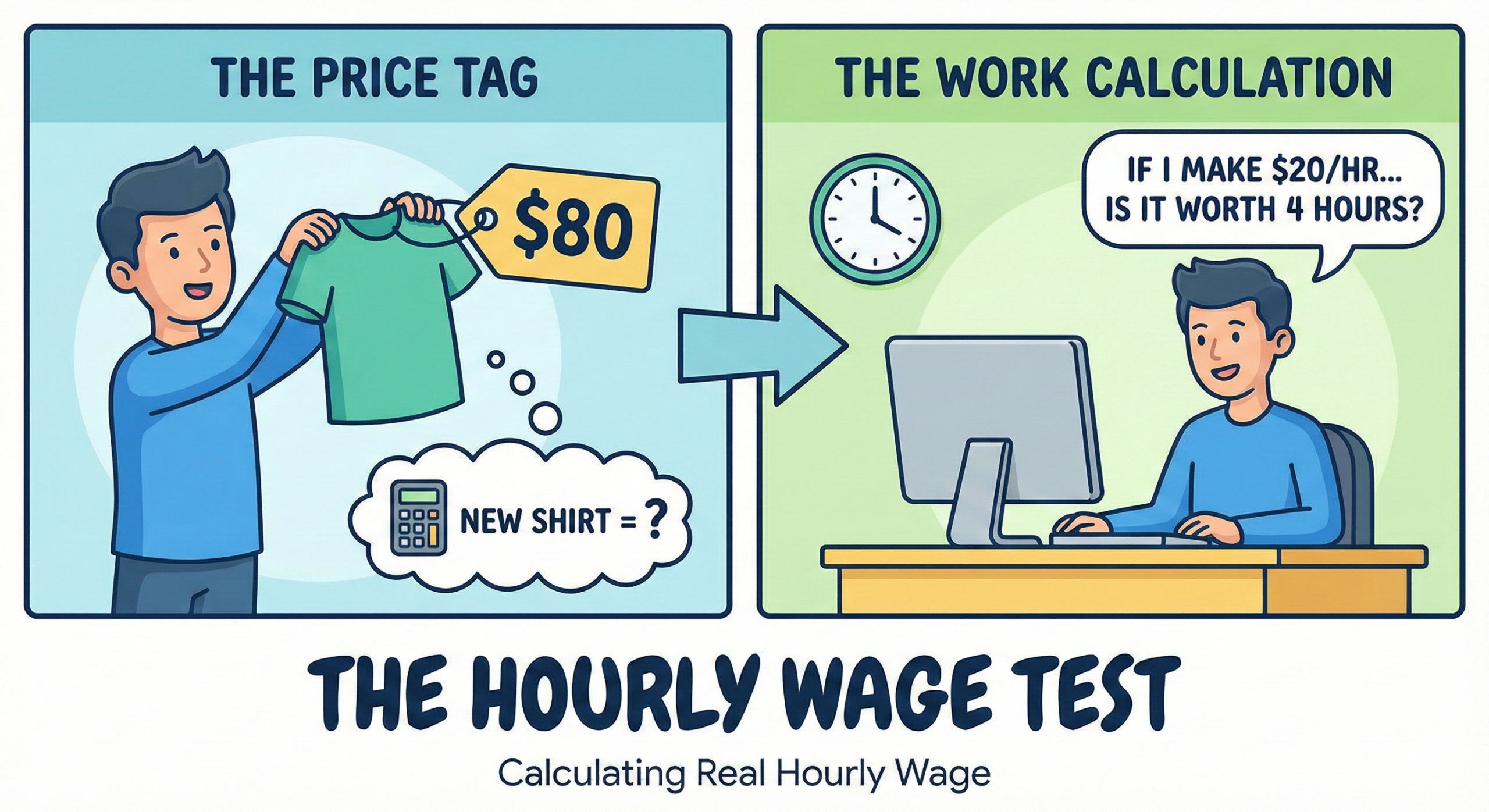

But then, a different thought intruded—a concept he had recently read about that nagged at the back of his mind like a splinter. He stopped looking at the $60 as currency. He stopped thinking about the digits on his banking app. Instead, he tried to translate that price tag into something far more finite and non-refundable: his time.

Leo worked as a junior analyst. His offer letter stated he made $25 an hour. Simple math suggested the shirt cost him a little over two hours of work. Two hours of sitting in a cubicle, answering emails, and staring at spreadsheets seemed like a fair trade for a shirt that made him look successful. It was a transaction he had made hundreds of times before without hesitation.

However, the new method of thinking—the “Real Hourly Wage” test—demanded he dig deeper. It asked him to consider the reality of his employment, not just the gross number on his pay stub. It required him to peel back the layers of his daily existence to find the true cost of his labor.

To earn that money, Leo woke up at 6:30 AM, an hour before he wanted to. He spent 45 minutes driving in gridlock traffic, burning gas and patience. He wore clothes he wouldn’t wear on a Saturday, which cost money to dry clean. He bought lunch near the office because he was too tired to pack one. When he got home, he was so drained he often ordered takeout and paid for streaming services to “zone out” and recover from the day.

Leo closed his eyes for a moment, standing there in the aisle, and ran the real numbers. After subtracting taxes, commuting costs, work attire, and the money spent coping with job stress, and then adding his unpaid commute time to his work hours, his “Real Hourly Wage” wasn’t $25. It was closer to $10.

Suddenly, the navy-blue shirt didn’t cost two hours of work. It cost six.

Six hours of his life—nearly a full workday—bartered away for a piece of cotton that would eventually fade and end up in a donation bin. Was the shirt worth waking up at 6:30 AM, sitting in traffic, and enduring office politics for six straight hours? Was it worth missing dinner with his friends? Was it worth the stiffness in his lower back from sitting in his ergonomic chair?

Leo put the shirt back on the rack. The price hadn’t changed, but the cost had.

This shift in perspective is the heart of the “Hourly Wage Test.” It is a tool that strips away the illusions of currency and reveals the true exchange taking place in every transaction: the trade of “Life Energy” for material goods. In a global economy where fast fashion, high-tech gadgets, and housing markets vie for our wallets, understanding this exchange is the single most important skill for financial survival.

The Definition of Life Energy

Money is often defined by economists as a medium of exchange, a unit of account, or a store of value. These definitions are useful for banks and governments, but they are abstract for the individual. The most accurate definition of money for a person earning a paycheck, as proposed by financial authors Vicki Robin and Joe Dominguez in their seminal work Your Money or Your Life, is simpler and more visceral: Money is something we trade our life energy for.1

“Life Energy” represents the limited time each person has on Earth. It is the most precious resource because it is the only one that is strictly non-renewable. You can print more money. You can borrow more money. You can invest money to make it grow. But you cannot print more time. Once an hour is spent earning a dollar, that hour is gone forever. It is deleted from your personal timeline.

Therefore, every purchase made is not just a financial transaction; it is a spiritual and physical transaction. When a consumer buys a car, a house, or a cup of coffee, they are paying with the hours, days, or years of life they surrendered to earn that cash. The “Life Energy” concept forces us to ask a terrifying but necessary question: Is this item worth the piece of my life I gave up to get it? 3

Part II: The Mathematics of Reality

The Illusion of the Gross Salary

Most people operate under a financial illusion created by their “gross income.” A salary of $50,000 a year or an hourly wage of $25 creates a sense of wealth and capacity that often does not match the reality of the bank balance at the end of the month. This discrepancy exists because employment carries “hidden costs”—expenses that are directly tied to the act of working but are rarely accounted for when calculating the value of a job.5

We tend to view our job as a faucet that pours money into our lives. We rarely stop to check the leaks in the pipes. These leaks are the costs we pay for the privilege of working. To understand the true cost of a purchase, one must first calculate their Real Hourly Wage. This figure is almost always significantly lower than the nominal wage stated in an employment contract.

Calculating the Real Hourly Wage

The calculation of the Real Hourly Wage requires a forensic accounting of one’s work life. It involves two main adjustments: adjusting the money earned downward (subtracting job-related expenses) and adjusting the time spent working upward (adding job-related time). This is the core exercise of the Your Money or Your Life program, specifically Step 2, which focuses on tracking life energy.1

Step 1: Adjusting Income (The Financial Cost of Working)

A job pays a salary, but it also demands payments back from the worker. These are costs that would not exist if the person did not hold that specific job. When Leo looked at his paycheck, he saw the gross number. But he had to subtract the following to find his actual take-home value:

- Taxes: The most obvious deduction. Federal, state, and local taxes immediately reduce the purchasing power of every hour worked. Depending on the country and bracket, this can remove 20% to 40% of the energy expended immediately.

- Commuting Costs: Gas, wear and tear on a vehicle, parking fees, tolls, or public transit fares are direct subsidies the worker pays to their employer to show up. If a job requires a car, the car payment and insurance are partially work expenses.

- Costuming: Many jobs require specific attire. For a construction worker, it might be steel-toed boots. For a lawyer, it is a suit. For a retail worker, it is a uniform. These items often have little utility outside the workplace. You don’t wear your steel-toed boots to the beach. You don’t wear your high-stress business suit to watch a movie on the couch. Dry cleaning and laundering these items are additional ongoing costs.1

- Work-Related Meals: The cost difference between a home-cooked meal and a lunch bought at a cafeteria or restaurant near the office is a work expense. If a packed lunch costs $3 and a bought lunch costs $15, the job is costing the worker $12 a day just in food. Coffee runs to maintain energy levels during a mid-afternoon slump are also part of this category.

- Decompression Expenses: This is often the most overlooked category. It includes money spent to recover from the stress of the job. This is the “I deserve this” spending. It includes Friday night drinks to blow off steam, “retail therapy” to feel a sense of control, or expensive vacations needed to “escape” the grind. It also includes convenience services like house cleaning, landscaping, or takeout ordered because the worker is too exhausted to cook or clean after a long shift. If the job didn’t exhaust you, these expenses would likely disappear.1

Step 2: Adjusting Time (The Temporal Cost of Working)

A standard workweek is often cited as 40 hours. However, the time dedicated to the job is rarely limited to the hours between clocking in and clocking out. The employer “rents” 40 hours, but the job often “consumes” 50 or 60 hours.

- Commuting Time: The time spent traveling to and from work is time that belongs to the employer, effectively. It is time the worker cannot use for leisure, family, or sleep. If you drive an hour each way, that is 10 hours a week—an entire extra workday—that is unpaid.

- Preparation Time: The time spent showering, shaving, applying makeup, and dressing specifically for the job. If you spend 45 minutes getting “presentable” for the office, but would only spend 10 minutes getting ready on a Sunday, the difference is work time.

- Decompression Time: The hours spent collapsing on the couch after work, too tired to engage in hobbies or meaningful relationships, are a direct result of the energy drain of the job. If you need an hour of “vegetating” to recover from the stress of the office before you can talk to your spouse, that hour is a cost of employment.1

- Job-Related Illness: Time spent recovering from stress-induced headaches, back pain from sitting, or flus caught from coworkers in an open-plan office. This is time lost to the job.1

The Formula for Truth

The Real Hourly Wage is calculated by taking the Adjusted Weekly Income (Gross Income minus all work-related expenses) and dividing it by the Adjusted Weekly Hours (Standard work hours plus all work-related time).7

Real Hourly Wage = Gross Weekly Income – Taxes – Work Related Expenses (Paid Weekly Hours + Unpaid Work Related Time)

This formula is the “lie detector” of personal finance. It reveals that the high-paying job in the city with the long commute and the expensive suits might actually pay less per hour of life energy than a modest job close to home where you can wear jeans and walk to work.

Case Study: The “High Earner” Trap

To fully understand the impact of this calculation, let’s look at a detailed example. Consider a marketing manager named Sarah. Her salary is $80,000 a year, which breaks down to roughly $40 an hour. She feels successful. She buys premium brands. However, the Hourly Wage Test reveals a different story.

Financial Adjustments (Weekly):

- Gross Income: $1,540 (after taxes approx. $1,150)

- Commuting (Gas/Parking/Tolls): -$100. Sarah drives into the city and pays for a garage.

- Professional Wardrobe: -$50. She buys new outfits seasonally to stay trendy in her fashion-conscious office.

- Lunches/Coffee: -$75. She buys a latte every morning and a salad or sandwich for lunch.

- Decompression (Takeout/Entertainment): -$100. She orders Uber Eats three times a week because she is too tired to cook.

- Job-Maintenance Total: -$325

- Adjusted Weekly Income: $825

Time Adjustments (Weekly):

- Official Hours: 40 hours.

- Commute (5 hours round trip x 5 days): +10 hours.

- Getting Ready (1 hour/day): +5 hours.

- Decompression/Venting: +5 hours. She spends an hour a day scrolling social media just to numb her brain after work.

- Total Life Energy Spent: 60 hours.

The Calculation:

$825/ 60 hours = $13.75 per hour

Sarah believes she earns $40 an hour. The reality is that her Real Hourly Wage is $13.75. When she considers buying a new designer handbag for $200, she thinks it costs her 5 hours of work ($200 / $40). In reality, it costs her nearly 15 hours of life energy ($200 / $13.75). That is almost two full days of work for one accessory.

When Sarah realizes this, the handbag suddenly seems much heavier. It represents two days of her life she will never get back. Is the leather strap worth two days of freedom?.1

Part III: The Psychology of Paying with Time

Time vs. Money: The Mental Accounting

The human brain is a fascinatingly flawed machine when it comes to value. Behavioral economics suggests that humans process time and money differently. Research indicates that while people are generally risk-averse with money, they can be more reckless with time.

A study on consumer psychology found that participants were more willing to take high-variance gambles when paying with time rather than currency. For example, people might hesitate to spend $20 on a lottery ticket, but they will happily spend 20 minutes filling out a survey for a chance to win a prize. This phenomenon occurs because money is concrete and finite in the immediate sense—if you spend $50, it is physically gone from your wallet. Time, however, feels ambiguous and open-ended. It feels “free” because we don’t physically hand it over.10

This “flexible valuation” of time leads consumers to undervalue their own life energy. A consumer might drive 45 minutes to a different store to save $10 on a household item. If they calculated their Real Hourly Wage, they might realize that their time is worth $20 an hour. By driving 45 minutes there and back (1.5 hours total) to save $10, they have effectively spent $30 of life energy to save $10 of currency. They have lost $20 in the transaction, yet they feel like they “won” because they paid less cash.

The “Poverty Penalty” on Time

The Hourly Wage Test also reveals deep inequalities in our society. Low-income workers often face a “double tax” on their life energy. Not only is their hourly rate lower, but the goods they purchase consume a staggering percentage of their total available time. This is often referred to as the “poverty penalty”.12

For a corporate lawyer earning $300 an hour, a $5 loaf of bread costs 1 minute of work. It is negligible. For a minimum wage worker earning $7.25 an hour, that same loaf costs over 40 minutes of work. The goods cost the same in currency, but the cost in life experience is vastly different. The lower the wage, the more “life” must be sold to sustain survival.

This creates a vicious cycle. Low-wage workers have to spend so much of their life energy just to secure basics—food, rent, transport—that they have no time left to “invest” in themselves. They lack the time to get an education, to exercise, to sleep enough, or to network for better jobs. They are trapped in a state of “time poverty.” While the wealthy have money to buy time (hiring cleaners, taking fast transport), the poor must sell their time to buy survival.13

Part IV: The Global Hourly Wage Test

If we expand Leo’s realization to the entire world, the picture becomes even more complex. We live in a globalized economy where prices for many goods—like iPhones, branded sneakers, or Big Macs—are somewhat standardized, but wages are not. Applying the Hourly Wage Test globally offers a stark view of purchasing power and economic disparity.

The Burger Benchmark: The Big Mac Index

One of the most famous tools for measuring this disparity is the Big Mac Index, created by the magazine The Economist. It was designed to measure “Purchasing Power Parity” (PPP)—the idea that exchange rates should adjust so that a basket of goods costs the same everywhere. However, it also serves as a perfect “Hourly Wage Test” for the common worker.14

A Big Mac is a standardized product. It requires the same ingredients and roughly the same effort to produce whether it is made in Chicago or Cairo. But the time it takes to earn one varies wildly.

In 2018, data showed the disparity in work-time required to buy this burger:

- Hong Kong / Tokyo: A worker might need only 10 to 15 minutes of labor to afford a Big Mac. For them, it is a trivial snack.

- United States (Major Cities): The average is roughly 10 to 20 minutes.

- Jakarta: The same burger might require over 100 minutes of work.15

Think about that difference. When a worker in Nairobi or Jakarta buys a Big Mac, they are trading nearly two hours of their life for it. A worker in Los Angeles trades 10 minutes. The burger is the same, but the “life cost” is ten times higher in the developing world. For the worker in Nairobi, that burger represents a significant investment of their daily energy, whereas for the American, it is barely a blip in their day.

The High-Tech Yardstick: The iPhone Index

In the modern era, the smartphone is a necessity, not a luxury. It is the portal to the economy, to information, and to social connection. The iPhone Index, published by the analytics firm Picodi, calculates the number of days an average citizen in various countries must work to afford the latest flagship iPhone (e.g., the iPhone 16 Pro). This index provides a brutal visualization of the Real Hourly Wage on a global scale.16

The 2024 Landscape:

- Switzerland: The average worker is the “richest” in time. They need to work just 4 days to buy the phone. It is less than a week’s effort.

- United States: It takes approximately 5.1 days. Still very affordable—essentially one work week.

- Australia & Singapore: Around 5.7 days.

- Malaysia: It requires 25.3 days—more than a full working month. The phone costs 1/12th of their annual life energy.18

- Turkey: A staggering 72.9 days. A Turkish worker must labor for nearly three months—a quarter of the year—just to own the phone.17

This comparison forces the user to ask a difficult question: Is the technology worth 20% of my working year? For a Swiss person, the answer is easily “yes.” For a Turkish person, the answer is complicated. If that Turkish worker has a “Real Hourly Wage” that accounts for commuting and stress, the cost might be closer to four or five months of actual life energy. The phone becomes a monumental sacrifice, displacing other potential purchases like better food, healthcare, or savings.

The Roof Over Your Head: The Housing Bubble Index

The ultimate purchase for most people is a home. It is the largest expenditure of life energy any individual will make. The UBS Global Real Estate Bubble Index analyzes housing markets in 25 major cities to see how “overvalued” they are compared to local incomes. Essentially, it measures how many years a skilled service worker must toil to buy a 60-square-meter apartment near the city center.19

The shift in “time cost” for housing has been dramatic and damaging.

- Zurich: Despite high wages, the cost of buying a home has risen by 25% in real terms over five years. It is becoming a luxury good. The “time price” is inflating.

- Miami: This city now holds the highest bubble risk. Prices have decoupled from local incomes. For a local worker in Miami, the dream of ownership is receding as the “time cost” skyrockets, driven by foreign investment and speculation.19

- Tokyo: Interestingly, Tokyo is categorized as “defensive” and resistant to change. While still expensive, the time-cost has remained more stable compared to the volatility of Western markets.22

When housing prices rise faster than wages, the population experiences a massive inflation in the life energy required to survive. A house that cost 10 years of labor in 1980 might cost 20 years of labor in 2025. This effectively shortens the “free life” of the worker by a decade. They must stay in the workforce ten years longer just to secure the same shelter their parents bought for half the time. This is the hidden crisis of the modern economy: we are living longer, but we are selling more of those years just to have a roof over our heads.

Part V: The Shirt on Your Back – A Global Supply Chain of Time

Returning to the narrative of Leo and his navy-blue shirt, there is another layer to the Hourly Wage Test that is often invisible: the life energy of the person who made the shirt.

Leo’s calculation focused on his own life energy. But the global economy is a complex web of time exchanges. The shirt Leo almost bought for $60 (6 hours of his real wage) likely originated in a country with a vastly different wage structure.

The Labor Cost Disparity:

- Switzerland/Europe: Labor costs in the textile industry can exceed $50 per hour. If the shirt were made here, it would cost hundreds of dollars.

- USA: Around $17 per hour.

- Bangladesh/Pakistan: As low as $0.62 per hour.23

If the shirt was made in Bangladesh, the worker who sewed it earned roughly 60 cents an hour. The $60 price tag represents 100 hours of that worker’s life energy.

There is a profound imbalance in this transaction. Leo trades 6 hours of his life to own an object that cost another human being 100 hours of their life to create. (Of course, the price includes materials, shipping, and corporate profit, but the scale of human time embedded in the object is vastly different).

This “Fast Fashion” model relies on the devaluation of life energy in the developing world. The low cost of the shirt is subsidized by the time-poverty of the garment worker. When consumers buy cheap, disposable clothing, they are often unaware that the low monetary price masks a high human cost.

Understanding this adds a moral dimension to the Hourly Wage Test. When we buy something, we are not just validating our own time; we are validating the system that priced the time of the producer. High-quality, fair-trade goods often cost more currency, but they represent a fairer exchange of life energy between the buyer and the maker.

Part VI: The Deep Dive into Hidden Costs

To accurately perform the Hourly Wage Test and reclaim agency, one must understand the “Hidden Costs” of employment in excruciating detail. These are the silent killers of wealth and time.

1. The Commute: The Silent Wage Killer

Commuting is the single most detrimental factor to the Real Hourly Wage. It is unpaid work. A one-hour commute each way adds 10 hours to the workweek—a 25% increase in time committed to the employer for zero additional pay.

- Direct Costs: Fuel is just the beginning. There is vehicle maintenance (tires, oil changes, repairs), insurance premiums that are higher for daily drivers, tolls, parking fees, or public transit passes.

- Indirect Costs: Research consistently shows that long commutes correlate with higher rates of obesity, divorce, and stress. The time spent in traffic is time not spent exercising or connecting with family. These lead to future medical costs and legal costs, which are essentially deferred costs of the current job. A bad back from driving 10 hours a week is a bill that will arrive 20 years later.1

2. The Cost of “Looking the Part” (Costuming)

“Costuming” extends beyond uniforms. It includes the “social uniform” of the workplace.

- Apparel: Suits, dress shoes, and accessories that are too formal for leisure wear. The “business casual” wardrobe requires constant updating to look professional.

- Grooming: Frequent haircuts, makeup, and personal care products purchased specifically to maintain a “professional appearance.”

- Status Signaling: In many corporate environments, there is implicit pressure to fit in. This might mean driving a certain brand of car (not an old beater) or having the latest smartphone. This is defensive expenditure—spending money to protect one’s standing in the office hierarchy so as not to be passed over for promotions.1

3. Convenience and Compensation Spending

When life energy is drained by the job, workers pay money to buy back functionality. This is the “tiredness tax.”

- Food: The tired worker orders pizza ($30) instead of cooking lentils ($2). They buy the $12 sandwich near the office because they didn’t have the energy to pack a lunch.

- Services: Hiring house cleaners, landscapers, or childcare is often necessary because the worker physically cannot be in two places at once. If you weren’t working 60 hours a week, you might enjoy gardening. But because you are working, you pay someone else $50 an hour to do it for you.

- Escapism: “I worked hard, I deserve this.” This phrase justifies spending on luxury items, alcohol, or expensive vacations designed solely to numb the exhaustion of the workweek. If the job wasn’t so draining, the need for expensive “escape” would diminish. A person who loves their life doesn’t need to pay thousands of dollars to escape it for a week.1

4. Health and Future Costs

Some costs are delayed. Sitting in a chair for 40 years contributes to cardiovascular disease. Heavy lifting ruins backs. Exposure to chemicals in industrial jobs shortens lifespans. These are debts accrued by the body that will eventually be paid in medical bills and reduced quality of life in retirement. While hard to calculate on a weekly ledger, they are a very real deduction from the Real Hourly Wage. The “hidden cost” here is literally the shortening of your life.27

Part VII: Breaking the Cycle – Strategies for Reclaiming Life Energy

The goal of the Hourly Wage Test is not to depress the reader, but to empower them. Once the Real Hourly Wage is known, it becomes a powerful filter for decision-making. It is the core of the Your Money or Your Life program’s 9-step process for Financial Integrity.

1. Calculate Your Number (Step 2)

Every worker should perform the calculation. It is the foundation of truth.

- Track: Keep a record of every cent earned and spent.

- Adjust: Subtract all job-related expenses (transit, clothes, meals, escape spending) from your income.

- Add Time: Add all job-related hours (work + commute + prep + decompress) to your work week.

- Divide: Adjusted Income / Adjusted Hours = Real Hourly Wage.

- Visualize: Write this number on a small card and put it in your wallet next to your credit card. This is your reality.7

2. The “Worth It?” Moment (Step 3 & 4)

When standing in a store (like Leo), use the number. Divide the price by your Real Hourly Wage.

- Scenario: You want a new video game console for $500. Your Real Wage is $10.

- Math: $500 / $10 = 50 Hours.

- Question: Is this console worth sitting in a cubicle for more than a full week? Is it worth missing 50 dinners with my family? Is it worth 50 hours of stress?

If the answer is yes, buy it without guilt. You have accepted the trade. If the answer is no, walk away. You have just saved 50 hours of your life. This aligns spending with values.4

3. Reducing Job-Related Costs

Increasing the Real Hourly Wage doesn’t always require a raise from the boss. It can be achieved by lowering the costs of working.

- Telecommuting: Working from home eliminates the commute time and cost, immediately boosting the Real Hourly Wage. It also reduces costuming and lunch costs.

- Brown-Bagging: Bringing lunch saves thousands of dollars a year (hundreds of hours of life energy).

- Simplifying Wardrobe: Adopting a “capsule wardrobe” reduces costuming expenses and decision fatigue.2

- Living Closer: Moving closer to work might cost more in rent, but if it eliminates the need for a car, the trade-off in life energy (time saved commuting) might make the Real Hourly Wage skyrocket.

4. The End Game: Financial Independence (Steps 8 & 9)

The ultimate application of this philosophy is Financial Independence (FI). By lowering expenses and valuing life energy over material goods, savings rates increase. Step 8 of the program involves tracking “Capital and the Crossover Point.”

- Capital: The money you save is invested. It starts to earn its own money (interest/returns).

- Crossover Point: Eventually, the monthly income from your investments surpasses your monthly expenses.

At this point, the Real Hourly Wage becomes infinite. Why? Because the work requirement drops to zero. You no longer have to trade any life energy for money. You have bought back all your remaining years. The individual is free to work because they love it, or not work at all. This is the ultimate goal of the Hourly Wage Test: to reach a point where you never have to sell your time again.4

Conclusion: The Final Calculation

Leo stood in the department store, the shirt still in his hand. The math was done. The shirt cost $60. His Real Hourly Wage was $10.

Buying the shirt meant he had worked Monday morning until Monday afternoon solely for this piece of cloth. It meant 45 minutes of traffic. It meant swallowing his pride when his boss made a snide comment. It meant a cold sandwich at his desk. It meant the headache he had fought off at 3 PM.

He looked at the shirt. It was just cotton. It wasn’t worth the traffic. It wasn’t worth the stress. It wasn’t worth the headache.

He hung the shirt back on the rack. As he walked out of the store empty-handed, he didn’t feel poorer. He felt richer. He had just bought himself six hours of freedom.

The Hourly Wage Test is more than a calculator; it is a mirror. It forces us to confront the reality that we are not paying with money—we are paying with our lives. In a world obsessed with the price of everything, it is the only way to understand the value of anything.

Whether checking the price of a burger in Zurich, an iPhone in Mumbai, or a shirt in a local mall, the question remains the same: Is this worth my life?

When we learn to answer that question honestly, we stop being consumers and start being the owners of our own time. And time, unlike a faded blue shirt, is the one thing we can never return.

Appendix: Global Indices Data Summary

| Index | What it Measures | Highest “Time Cost” (Work Required) | Lowest “Time Cost” (Work Required) |

| Big Mac Index | Minutes to earn a burger | Kenya, Indonesia, Mexico (100+ min) | Hong Kong, Japan, USA (10-15 min) |

| iPhone Index | Days to earn flagship iPhone | Turkey (72.9 days), Philippines (68.8 days) | Switzerland (4 days), USA (5.1 days) |

| Housing Bubble | Bubble Risk (Years to buy) | Miami (High Risk), Tokyo (High but stable) | Cities with fair value (lower risk) |

| Textile Labor | Hourly wage of garment worker | Bangladesh ($0.62/hr) | Switzerland ($50+/hr) |

Data compiled from Picodi iPhone Index 2024, The Economist Big Mac Index, UBS Global Real Estate Bubble Index, and Werner International Labor Cost comparisons. 15

Appendix: The Real Hourly Wage Worksheet

| Category | Monthly Estimate |

| A. Monthly Gross Income | $__________ |

| B. Deductions (Taxes, SS, etc.) | -$__________ |

| C. Job-Related Costs | |

| 1. Commuting (Gas, Bus, Car upkeep) | -$__________ |

| 2. Costuming (Uniforms, Dry Cleaning) | -$__________ |

| 3. Meals at Work | -$__________ |

| 4. Job-Related Escape/Entertainment | -$__________ |

| 5. Medical costs due to job stress | -$__________ |

| D. Total Adjusted Income (A – B – C) | $__________ |

| E. Monthly Work Hours | __________ hrs |

| F. Job-Related Time | |

| 1. Commuting Time | +__________ hrs |

| 2. Getting Ready Time | +__________ hrs |

| 3. Decompression Time | +__________ hrs |

| 4. Job-Related Illness/Worry | +__________ hrs |

| G. Total Adjusted Hours (E + F) | __________ hrs |

| REAL HOURLY WAGE (D ÷ G) | $__________ / hr |

Use this worksheet to determine the true value of your time. 7

Works cited

- Your Money or Your Life Summary, accessed December 2, 2025, https://yourmoneyoryourlife.com/book-summary/

- Make More Money By Reading: “Your Money or Your Life” by Vicki Robin and Joe Dominguez | by N Herman | Medium, accessed December 2, 2025, https://medium.com/@bigbussinessboys/make-more-money-by-reading-your-money-or-your-life-by-vicki-robin-and-joe-dominguez-80260ecc0ea8

- Dr. Tammie’s Book of the Month December 2024: Your Money or Your Life by Vicki Robin & Joe Dominguez – Pink Coat, MD, accessed December 2, 2025, https://pinkcoatmd.com/december-2024-your-money-or-your-life-by-vicki-robin-joe-dominguez/

- Book Review: Your Money or Your Life | White Coat Investor, accessed December 2, 2025, https://www.whitecoatinvestor.com/your-money-or-your-life-both-please/

- LEVELUP! HIRING SYSTEM: THE COMPLETE GUIDE – Amazon AWS, accessed December 2, 2025, https://growyourbusinessseries.s3-ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/LevelUp!+Better+Hiring+System.pdf

- Managing staff costs – Pulse Today, accessed December 2, 2025, https://www.pulsetoday.co.uk/news/practice-personal-finance/managing-staff-costs/

- FI_Goup_Study_Workbook_2009-03-31 – Vicki Robin, accessed December 2, 2025, https://vickirobin.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/FI_Goup_Study_Workbook_2009-03-31.doc

- Book Review: Your Money or Your Life – The Fioneers, accessed December 2, 2025, https://thefioneers.com/your-money-your-life/

- 9 Steps to Transforming Your Relationship With Money and Achieving Financial Independence – AddictBooks, accessed December 2, 2025, https://files.addictbooks.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Your-Money-or-Your-Life.pdf

- Spending Time versus Spending Money – Wharton Faculty Platform, accessed December 2, 2025, https://faculty.wharton.upenn.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/Spending-time-vs-money.pdf

- Sunk Cost Effects of Time and Effort: Enjoyment of Effort as a Moderator – University of Idaho, accessed December 2, 2025, https://verso.uidaho.edu/view/pdfCoverPage?instCode=01ALLIANCE_UID&filePid=13308677430001851&download=true

- Helping Buyers Beware: The Need for Supervision of Big Retail – Scholarly Commons at Boston University School of Law, accessed December 2, 2025, https://scholarship.law.bu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1028&context=faculty_scholarship

- Economic Security in Nova Scotia – the Centre for the Study of Living Standards, accessed December 2, 2025, http://csls.ca/reports/csls2008-05.pdf

- Big Mac Index – Wikipedia, accessed December 2, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Big_Mac_Index

- [OC]Average Working time required to buy a Big Mac in cities worldwide (2018) – Reddit, accessed December 2, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/dataisbeautiful/comments/r1onb8/ocaverage_working_time_required_to_buy_a_big_mac/

- iPhone Index 2024: How Many Days You Need to Work to Afford It – Picodi.com, accessed December 2, 2025, https://www.picodi.com/us/bargain-hunting/iphone-index-2024

- How many days of work does it take to buy an iPhone 16? India ranks high on the list, accessed December 2, 2025, https://www.financialexpress.com/life/technology-how-many-days-of-work-does-it-take-to-buy-an-iphone-16-india-ranks-high-on-the-list-3617059/

- iPhone Index 2024: How Many Days M’sians Need to Work to Afford It – Bargain Hunting, accessed December 2, 2025, https://www.picodi.com/my/bargain-hunting/iphone-index-2024

- UBS Global Real Estate Bubble Index 2024: Miami on top, accessed December 2, 2025, https://www.ubs.com/global/en/media/display-page-ndp/en-20240924-gebri24.html

- UBS Global Real Estate Bubble Index – Elements by Visual Capitalist, accessed December 2, 2025, https://elements.visualcapitalist.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/ubs-global-real-estate-bubble-index-2024.pdf

- Mapped: The World’s Most Unaffordable Housing Markets – Visual Capitalist, accessed December 2, 2025, https://www.visualcapitalist.com/mapped-the-worlds-most-unaffordable-housing-markets/

- Chart: Global Risk of Housing Bubbles Deflates Sharply | Statista, accessed December 2, 2025, https://www.statista.com/chart/19556/cities-on-housing-bubble-index/

- Labour Cost Comparison Werner International Paves Way for Evaluation – Apparel Resources India, accessed December 2, 2025, https://in.apparelresources.com/business-news/sustainability/labour-cost-comparison-werner-international-paves-way-evaluation/

- Exploring economics: the secret life of t-shirts: 3.3 Labour costs | OpenLearn, accessed December 2, 2025, https://www.open.edu/openlearn/society-politics-law/exploring-economics-the-secret-life-t-shirts/content-section-3.3

- 2014 World Textile Industry Labor Cost Comparison, accessed December 2, 2025, https://shenglufashion.com/2015/01/25/2014-world-textile-industry-labor-cost-comparison/

- Fast fashion: what are the true costs? – Economics Observatory, accessed December 2, 2025, https://www.economicsobservatory.com/fast-fashion-what-are-the-true-costs

- Q&A: Tariff Impacts on Apparel Workers and Fashion Industry | The ILR School, accessed December 2, 2025, https://www.ilr.cornell.edu/news/public-impact/qa-tariff-impacts-apparel-workers-and-fashion-industry

- Your Money or Your Life | PDF | Balance Sheet | Market Liquidity – Scribd, accessed December 2, 2025, https://www.scribd.com/document/96829488/55566246-26330804-Your-Money-or-Your-Life