Part I: The Tale of Two Trajectories

The alarm buzzed at 6:30 AM in two different apartments, signaling the start of a Tuesday that would look remarkably similar on the surface, but vastly different underneath.

In apartment 4B, Arthur woke up feeling like he hadn’t slept at all. His head was heavy, a sensation he had come to accept as part of “getting older,” even though he was only thirty-two. The remnants of a late-night meal—a double cheeseburger and fries he had picked up on the way home—sat heavy in his stomach. He hit the snooze button, once, then twice, bargaining for just ten more minutes of rest. When he finally dragged himself out of bed, he was already behind schedule. There was no time to make coffee, let alone breakfast. He dressed hurriedly, his belt feeling a notch tighter than it had last month, and rushed out the door.

Arthur’s commute was a haze of brake lights and radio chatter. His stomach growled, a hollow, demanding ache. He pulled into the drive-thru of a popular fast-food chain near his office. It was a habit born of necessity, he told himself. It was fast. It was cheap. For $8.50, he got a large coffee, a sausage and egg sandwich on a croissant, and a hash brown. He ate it in the car, wiping the grease on a napkin as he steered with his knees. The salt and fat hit his system immediately, waking him up better than the caffeine. He felt ready for the day.

Across town, in apartment 2A, Elias woke up five minutes before his alarm. He stretched, feeling the morning sun hit the floorboards. He walked into his kitchen, which smelled faintly of spices—cumin, garlic, and onions. The night before, while watching the news, he had thrown a pound of black beans, an onion, and some spices into a slow cooker. Total prep time: five minutes. Now, the beans were tender and rich. He scooped a ladleful into a glass container, added a cup of brown rice he had cooked in a large batch on Sunday, and topped it with a handful of spinach.

For breakfast, Elias ate a bowl of oatmeal made with water and a sliced banana. The cost of his breakfast was roughly $0.45. The cost of his packed lunch was about $1.40. He drank a glass of water, grabbed his bag, and walked to the train station. He felt light, his mind clear.

The divergence between Arthur and Elias widened as the clock struck noon.

Arthur sat in the company cafeteria with his colleagues. They decided to order out. “It’s been a long morning,” one said. “Let’s get burgers.” Arthur agreed. The “value meal” was $12.00. It included a quarter-pound burger with cheese, a large fry, and a 32-ounce soda. As he ate, he did the mental math. Twelve dollars for a meal that kept him full was a good deal, he thought. A salad at the boutique place next door was $16.00. He was saving money.

Elias sat in the breakroom, heating up his container. The beans and rice weren’t glamorous. They didn’t have the engineered crunch of a french fry or the rush of high-fructose corn syrup. But as he ate, his body began a slow, steady process of digestion. The fiber in the beans meant the energy was released slowly, like a slow-burning log on a fire.

The turning point of the day arrived at 3:00 PM.

Arthur was staring at a spreadsheet that seemed to be swimming before his eyes. The massive spike in blood sugar from his lunch had triggered a flood of insulin, and now his glucose levels were crashing. His brain, starved of fuel, was shutting down. He felt irritable. A simple email from his boss felt like a personal attack. To power through, he went to the vending machine. A candy bar and an energy drink: $4.50. It was the only way to wake up his brain for the 4:00 PM meeting.

Elias was in the same meeting. He listened intently, taking notes. His energy levels were flat—no peaks, no valleys. He suggested a solution to a supply chain issue that had stumped the team all week. His boss nodded, impressed. Elias didn’t need a candy bar; his lunch was still fueling him, the complex carbohydrates providing a steady stream of glucose to his brain.

By 6:00 PM, Arthur was exhausted. He had spent $25.00 on food and drinks that day. He was too tired to cook, so he ordered a pizza for dinner ($22.00). Elias went for a run, then ate leftovers for dinner. His total food spend for the day was under $5.00.

Fast forward ten years.

The difference was no longer just about daily spending. Arthur, now 42, had been passed over for two promotions. His “afternoon slumps” had been noticed; he was seen as low-energy, unreliable in a crisis. More critically, the daily tax on his biology had compounded. He had been diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes three years ago. His medication, even with insurance, cost him $200 a month. He needed a CPAP machine for sleep apnea. His knees hurt, limiting his mobility.

Elias was a Director of Operations. He had saved the $20 daily difference between his diet and Arthur’s. That $7,300 a year, invested with compound interest, had grown into a down payment on a house. He had zero daily prescriptions. His biggest health expense was a gym membership.

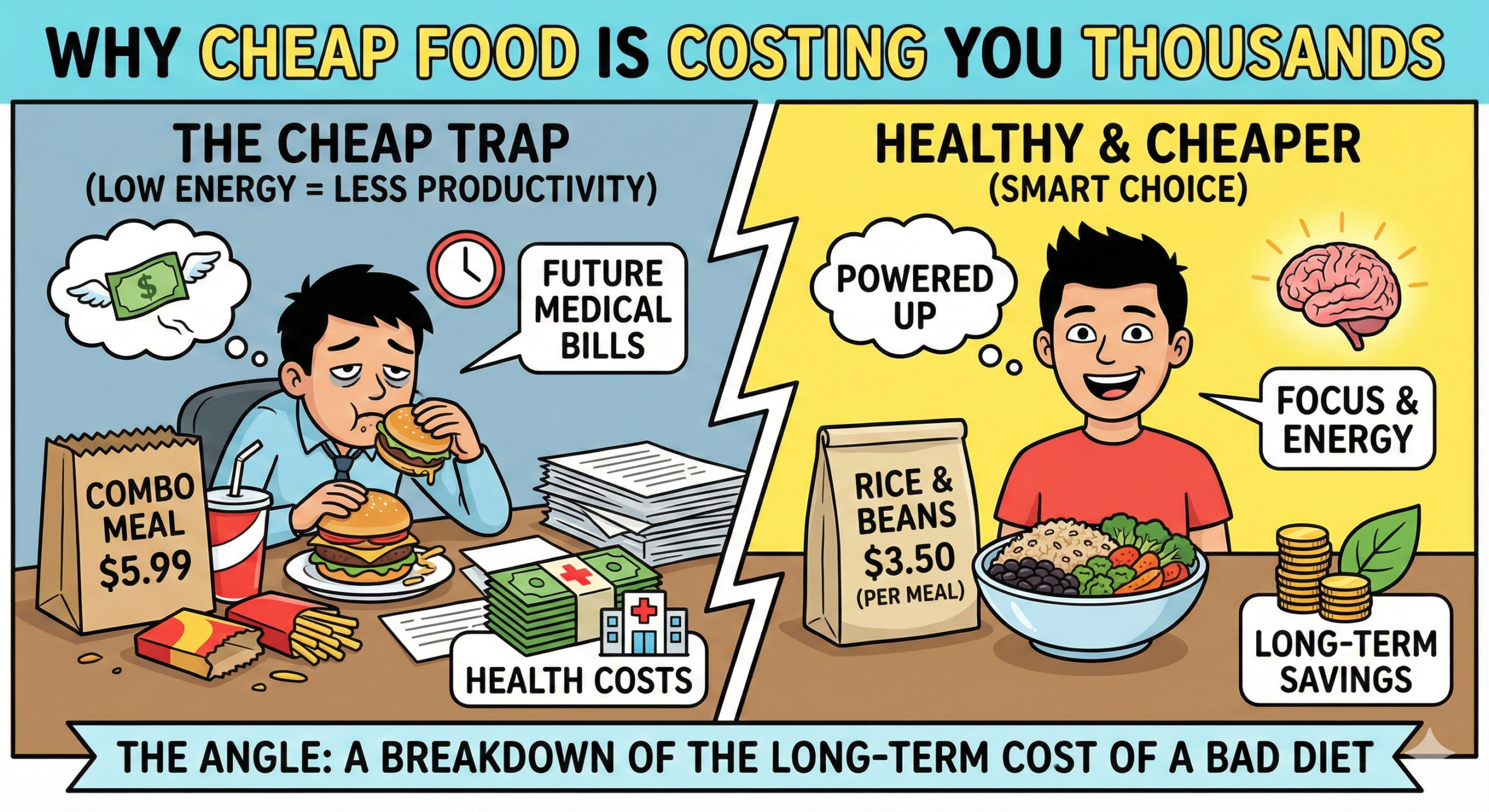

This story illustrates the “Fast Food Paradox.” We are conditioned to believe that fast food is the “cheap” option for the working class, a necessary evil for those with little time or money. But when we strip away the marketing and look at the hard economic and biological data, the truth is the opposite. The “value meal” is a high-interest loan taken out against your future health and earnings. This report will break down that loan, penny by penny, cell by cell.

Part II: The Mathematics of the Menu

To understand why the paradox exists, we must first dismantle the most persistent myth in the food industry: that healthy food is expensive and fast food is cheap. This belief drives millions of purchasing decisions every day, yet it crumbles under scrutiny when we analyze the price per nutrient rather than the price per calorie.

The Illusion of the Sticker Price

Consumers often compare the price of a fast-food meal to the price of premium, organic, or out-of-season produce. When a shopper sees a small container of organic blueberries selling for $6.00 and compares it to a hamburger selling for $2.00, the conclusion seems obvious: healthy food is a luxury.

However, this is a false comparison. The true economic competitor to the fast-food burger is not the organic blueberry, but the global staples of survival: grains and legumes. When we compare the commercial “value meal” against these staples, the markup on fast food becomes evident.

According to global agricultural pricing data from 2024, the cost of raw ingredients for a nutritious home-cooked meal is a fraction of the cost of processed food.

Table 1: Global Cost Comparison of Staple Foods vs. Fast Food (2024/2025 Estimates)

| Food Item | Market Price (Global Avg) | Cost Per Serving | Source |

| Dried Beans (1kg) | $1.60 – $2.67 USD | $0.16 – $0.27 | 1 |

| White Rice (1kg) | $0.28 – $1.81 USD | $0.03 – $0.18 | 2 |

| Home Meal (Rice + Beans) | — | $0.19 – $0.45 | — |

| Fast Food Combo Meal | — | $6.00 – $12.00 | — |

| Big Mac (USA) | $5.69 USD | $5.69 | 3 |

| Big Mac (Switzerland) | $8.17 USD | $8.17 | 3 |

| Big Mac (India) | — | ~$2.50 – $3.00 | 4 |

The data reveals a stark reality: A consumer in the United States or Europe paying $12.00 for a combo meal is paying approximately 2,500% more than the cost of a basic nutritional serving of rice and beans prepared at home.2 Even in countries where fast food is cheaper, such as India or Indonesia, the cost of purchasing prepared food remains significantly higher than the cost of raw ingredients.

In 2025, inflation trends have exacerbated this gap. The Consumer Price Index indicated that while the cost of groceries (food at home) rose by a modest 1.6%, the cost of eating out jumped by 3.6%.6 This “inflation gap” means that the convenience of the drive-thru is becoming an increasingly exclusive luxury, despite being marketed as a budget option.

The Big Mac Index: A Global Ruler

Economists use the “Big Mac Index” to compare the purchasing power of currencies, but for our purposes, it serves as a global barometer for the cost of processed food. It standardizes the “price of lunch” across borders.

- High-Cost Nations: In Switzerland, a single burger costs over $8.00 USD. In Uruguay, it is over $7.00.

- Moderate-Cost Nations: In the United States, the price sits around $5.69.

- Low-Cost Nations: In Egypt and India, the price drops to around $2.50 – $3.00.3

However, these prices must be contextualized by local income. In the Global South, while the dollar amount of a burger is lower, the relative cost to a worker’s daily wage is astronomical. A report by the World Food Programme (WFP) titled “Counting the Beans” highlights this disparity vividly.

In New York State, the ingredients for a simple plate of bean stew cost a worker 0.6% of their daily income. In South Sudan, that same plate of food costs a worker 201% of their daily income.7

This creates a perverse economic trap. In wealthy nations, fast food is cheap relative to income, making it an easy trap to fall into. In developing nations, Western-style fast food is an aspirational luxury, while the local population struggles to afford even the basic beans. In both cases, the “value” proposition is distorted.

The “Time Tax” Calculation

The most common defense for buying fast food is the “Time Tax.” The argument is simple: “I earn $20 an hour. If it takes me an hour to cook, that meal costs $20 in labor. Therefore, buying a $10 burger saves me money.”

This logic, however, is flawed on two counts:

- Passive vs. Active Time: Cooking staples like beans and rice is largely passive. It takes five minutes to rinse beans and put them in a pot or slow cooker. The cooking process happens while the person is doing other things—working, sleeping, or relaxing. The “active labor” time is often less than 15 minutes.9

- The Commute Cost: We often forget the time spent acquiring fast food. Driving to the restaurant, waiting in the drive-thru line, and driving back can easily consume 20 to 30 minutes. In many cases, the time spent obtaining “fast” food exceeds the active time required to prepare a simple meal at home.

When we factor in the fuel costs of driving to a restaurant, the economic argument for fast food collapses entirely. A study of household economics suggests that unless a person’s hourly wage is exceptionally high, the savings from cooking basic staples almost always outweigh the convenience cost of dining out.9

Part III: The Biological Bankruptcy

The financial transaction at the cash register is only the first installment of the cost of a bad diet. The second installment is deducted directly from your biological bank account, often within hours of the meal. This is the physiological tax of the “sugar crash.”

The Engine of the Mind

The human brain is an incredibly energy-intensive organ. Despite weighing only a few pounds, it consumes about 20% to 25% of the body’s total glucose energy.11 It is a high-performance engine that requires high-octane fuel.

When we eat complex carbohydrates (like beans, oats, or brown rice), the body breaks them down slowly. The fiber acts as a regulator, releasing glucose into the bloodstream at a steady, manageable rate. This provides the brain with a consistent fuel source for hours.

The Mechanism of the Crash

When we consume a standard fast-food meal—typically high in refined flour (buns), sugar (soda/ketchup), and saturated fats (fries/patties)—the metabolic process is violent.

- The Spike: The refined carbohydrates are digested almost instantly. Glucose floods the bloodstream.

- The Panic: The brain and pancreas detect this dangerous surge. High blood sugar damages blood vessels, so the body treats it as an emergency. The pancreas releases a massive wave of insulin to scrub the sugar from the blood.13

- The Plunge: Because the insulin response is often an overcorrection, blood sugar levels plummet rapidly, dropping below baseline. This is called reactive hypoglycemia.

- The Starvation: The brain, suddenly deprived of its primary fuel source, sends out alarm signals. It triggers the release of stress hormones like cortisol and adrenaline to mobilize stored energy.

The Cognitive Cost

This biological rollercoaster manifests as the “afternoon slump.” It is not just a feeling of tiredness; it is a measurable state of cognitive impairment.

Research has shown that this fluctuation in glucose is linked to poor attention, memory deficits, and reduced cognitive function.12 A study tracking nearly 800 office employees found that productivity and accuracy decline significantly in the afternoon hours, with a spike in typing errors and a drop in computer activity.15

The brain on a “fast food cycle” is effectively functioning in a state of crisis management. It is prioritizing survival (getting more sugar) over higher-level tasks like complex problem solving, emotional regulation, or creative thinking.

The Long-Term Damage: Type 3 Diabetes?

The cost of this cycle is not just daily; it is cumulative. Over years, the constant flooding of the system with insulin leads to “insulin resistance.” The cells stop listening to the insulin signal. This is the hallmark of Type 2 Diabetes.

However, researchers are now exploring the link between insulin resistance and the brain, sometimes referring to Alzheimer’s disease as “Type 3 Diabetes.” High blood sugar over time damages the blood vessels in the brain, leading to vascular dementia and memory loss.11 The cheap burger you eat today contributes to the brain fog you feel at 3:00 PM, but it also lays the groundwork for the cognitive decline you may face at age 70.

Part IV: The Career Cost – Wages and Productivity

If we accept that diet affects brain function, it follows that diet affects work performance. And if it affects performance, it inevitably affects income. This is the “hidden tax” on wages that few people calculate.

The Productivity Gap

The link between nutrition and economic output is one of the most robust findings in health economics. Poor nutrition is a productivity killer.

- The 66% Gap: Employees with unhealthy diets are 66% more likely to report a loss in productivity compared to those who regularly consume whole grains, fruits, and vegetables.16

- The 93% Risk: Employees who rarely eat fruits and vegetables are 93% more likely to have a higher loss in productivity.16

This loss of productivity is often invisible. It is not necessarily about missing days of work (absenteeism), but about “presenteeism”—being at work but not fully functioning. It is the hour spent staring at a screen, unable to focus. It is the meeting where you zone out. It is the lack of energy to take on the extra project that leads to a promotion.

In the developing world, the cost is even higher. In Southeast Asia, iron deficiency alone accounts for a $5 billion loss in productivity annually.17 When a worker is malnourished (either from lack of food or from eating nutrient-poor junk food), their physical and mental capacity to work is capped.

The Obesity Wage Penalty

Beyond productivity, there is a darker economic reality: the labor market penalizes obesity. This phenomenon, known as the “Obesity Wage Penalty,” has been documented in multiple economic studies.

The penalty is not applied equally. It is largely a gendered issue.

- The Mechanism: This penalty persists even when controlling for other factors, suggesting it is partly driven by discrimination and societal stigma. In client-facing roles, employers may subconsciously (or consciously) bias against employees who do not fit a certain physical ideal.

- The Male Variance: For men, the data is more complex. Some studies suggest a “fat premium” for moderately overweight men, who may be perceived as authoritative. However, as obesity reaches Class III (severe obesity), the penalty returns, likely due to health-related absenteeism.18

Calculating the Career Loss

Let us return to our narrative of Arthur. If he earns $50,000 a year, a 9% wage penalty (or a loss of potential promotions due to 66% lower productivity) costs him $4,500 annually.

Over a 40-year career, assuming a standard 3% raise trajectory, this “Dietary Wage Gap” could amount to over $300,000 in lost earnings. This is money that is never earned, never invested, and never compounds. It is a ghost fortune, lost to the cumulative effects of daily lunch choices.

Part V: The Medical Mortgage

We have discussed the daily cost (lunch price) and the yearly cost (lost wages). Now we must address the lifetime cost: the medical bill. This is the massive debt that accumulates silently for decades before coming due.

The Diabetes Economy

Type 2 Diabetes (T2D) is the defining epidemic of the fast-food age. It is a disease of metabolic dysfunction driven primarily by diet and lifestyle. The costs associated with T2D are staggering.

In the United States, the total estimated cost of diagnosed diabetes in 2022 was $412.9 billion.20 To put that number in perspective, it is larger than the GDP of entire nations like Israel or Hong Kong.

For the individual, the cost is a personal financial crisis.

- Annual Cost: On average, a person with diabetes incurs annual medical expenditures of $19,736, of which approximately $12,022 is directly attributable to the disease.21

- The Breakdown: These costs come from medications (insulin prices have soared), frequent doctor visits, supplies (test strips, monitors), and treatment for complications (foot care, vision loss, kidney issues).

This is not a one-time fee. It is an annual rent paid to the pharmaceutical and medical industries for the rest of the patient’s life. Over a 20-year period, a diabetic patient may spend nearly $250,000 on managing their condition.

The Obesity Ledger

Obesity, often a precursor to diabetes, carries its own heavy price tag. The medical costs associated with obesity increase steeply with the severity of the condition (BMI Class).

- The Multiplier Effect: Adults with obesity pay $2,505 more per year in medical costs than those with normal weight.22

- Class III Costs: For those with severe obesity (Class III), the costs are even higher. The presence of obesity-related complications (like hypertension + diabetes) can increase medical costs by up to 5-fold.23

Table 2: Estimated Annual Medical Cost Increases by Condition (USA)

| Condition | Additional Annual Medical Cost | Source |

| Overweight (BMI 25-29) | Moderate Increase | 22 |

| Obesity (General) | + $1,861 – $2,505 | 22 |

| Diabetes (Type 2) | + $12,022 | 21 |

| Obesity + Diabetes + Hypertension | Up to 500% Increase | 23 |

The Cancer Connection

One of the most alarming recent findings is the link between “cheap” ultra-processed foods (UPFs) and cancer. A long-term study of nearly 100,000 adults found a direct correlation:

- Those with the highest consumption of UPFs had a 49% greater risk of being diagnosed with pancreatic cancer.

- They also had a 72% higher risk of developing colon cancer.25

Cancer is perhaps the most expensive disease to treat. The cost of chemotherapy, surgery, and radiation can easily bankrupt a family, even one with insurance. The “savings” of buying the cheaper processed meat (a Class 1 carcinogen) vanish the moment a diagnosis is made.26

Global Projections

This is not just a Western problem. The World Obesity Federation predicts that if current trends continue, the global economic impact of overweight and obesity will reach $4.32 trillion annually by 2035.27

By 2060, the global costs could reach $18 trillion. This is a global financial time bomb. Developing nations, whose healthcare systems are already fragile, will bear the brunt of this wave as they transition to Western-style diets.

Part VI: The Global Trap – Inequality and Access

While the story of Arthur and Elias focused on individual choice, we must acknowledge that for billions of people, the “Fast Food Paradox” is a trap set by systemic inequality.

The Food Gap and The Double Burden

The International Labour Organization (ILO) notes that the world is facing a “food gap” where one in six people is undernourished, and an equal number are obese.17 This creates the “Double Burden of Malnutrition.”

In many developing nations, we see a tragic irony: a child may be stunted due to lack of protein, while their parent is obese due to an excess of cheap, refined carbohydrates. This happens because the cheapest available calories are often sugar and oil, not protein and fiber.

The Geography of Affordability

The World Food Programme’s data on the “Cost of a Plate of Food” reveals the depth of this inequality.

- Global North: In New York, a simple bean stew costs 0.6% of a daily income. It is negligible.

- Global South: In South Sudan, the same meal costs 201% of a daily income.7

This disparity drives the paradox. In rich countries, processed food is cheap and ubiquitous, making it the “easy” choice. In poor countries, nutritious food is often unaffordable, forcing populations toward cheap, shelf-stable, ultra-processed imports as soon as they become available.

Food Deserts and Swamps

Even in wealthy nations, geography dictates destiny. “Food Deserts” are areas where fresh food is physically inaccessible—neighborhoods without grocery stores. Residents may have to take two buses to buy a head of lettuce but can walk to three fried-chicken shops.

In these environments, the “Time Tax” we discussed earlier becomes very real. If buying beans requires a two-hour round trip on public transit, the fast-food option becomes the rational economic choice in the short term, despite the long-term devastation.

The Macroeconomic Hit

The aggregate effect of this paradox slows down entire economies.

- GDP Loss: Studies estimate that obesity costs countries between 0.8% and 2.4% of their GDP.28

- Future Loss: By 2060, countries like Thailand could lose nearly 5% of their GDP to obesity-related costs.28

- Human Capital: The World Bank warns that malnutrition (both under- and over-nutrition) destroys human capital. A child who grows up on a nutrient-poor diet has lower cognitive development, earns less as an adult, and contributes less to the economy. This costs many developing countries 2-3% of their GDP annually.29

Part VII: The Investment Strategy – Breaking the Cycle

The data is overwhelming: the “Fast Food” lifestyle is a financial liability. It drains cash daily, saps earning potential yearly, and incurs massive debts continuously. So, how do we escape the trap? We must reframe our view of food. We must stop viewing lunch as a consumable expense and start viewing it as a capital investment.

The “Rice and Beans” Portfolio

If we view diet as an investment portfolio, the “Rice and Beans” strategy is the equivalent of a low-risk, high-yield index fund.

- Low Entry Cost: As established, the raw materials cost less than $0.50 per serving.

- High Yield: The combination provides complete protein (all essential amino acids) and high fiber.

- Stability: The complex carbohydrates provide stable blood sugar, ensuring consistent productivity (the “dividend”).

Transitioning to this diet does not require a chef’s skills. It requires a shift in logistics. Buying in bulk (5kg bags of rice/beans) reduces costs further. Using technology (slow cookers, pressure cookers) reduces the active time tax.

Policy Interventions

Governments are beginning to realize they cannot afford the future medical bills of their populations. The “exit strategy” requires policy shifts:

- Sugar Taxes: Countries like Mexico and the UK have implemented taxes on sugar-sweetened beverages. Evidence suggests this reduces consumption and generates revenue that can be used for health programs.30

- Subsidies Reform: Currently, many governments subsidize corn and soy, which makes high-fructose corn syrup and soybean oil (key ingredients in fast food) artificially cheap. Shifting these subsidies to fruits, vegetables, and legumes could flip the price dynamics.31

- Workplace Wellness: Employers are realizing that feeding their staff well pays off. Studies show that comprehensive workforce nutrition programs can boost productivity by up to 20%.32

Conclusion: The True Bill

When the cashier at the fast-food window asks for $12.00, they are only asking for the down payment. The true bill arrives in installments over the rest of your life.

It arrives on the Tuesday afternoon when you are too tired to finish the report that would have secured your promotion. It arrives in the unseen percentage of your paycheck that vanishes due to the “obesity penalty.” It arrives in the pharmacy line when you pay for the insulin that keeps you alive. And it arrives in the years of life lost—time that cannot be bought back at any price.

The story of Arthur and Elias is not just a parable of two lunches; it is a forecast of two economic futures. The “Fast Food Paradox” reveals that the products marketed to us as “cheap” and “efficient” are, in reality, luxury goods for the reckless. They borrow energy from tomorrow to pay for today.

Conversely, the simple, unglamorous staples—rice, beans, lentils, vegetables—are the true builders of wealth. By opting for the slow-cooked over the fast-fried, we are not just saving a few dollars at the grocery store. We are protecting our brains, securing our careers, and saving hundreds of thousands of dollars in future liabilities.

In the global economy of health, the most expensive meal you will ever eat is the one that costs you your future.

Appendix: Data Tables and Detailed Comparisons

Table 3: Lifetime Cost Model (Hypothetical 40-Year Projection)

| Category | Fast Food Lifestyle | Whole Food Lifestyle | Difference |

| Daily Food Cost (Avg) | $25.00 | $5.00 | -$20/day |

| Annual Food Cost | $9,125 | $1,825 | $7,300/yr saved |

| 40-Year Food Cost | $365,000 | $73,000 | $292,000 saved |

| Medical Costs (Diabetes/Obesity) | ~$240,000 (Lifetime Est) | ~$20,000 (Preventative) | $220,000 saved |

| Wage Penalty/Productivity Loss | ~$300,000 (Est) | $0 | $300,000 gained |

| TOTAL LIFETIME IMPACT | -$905,000 | Baseline | ~$812,000 Advantage |

Table 4: Nutrient Cost Efficiency Analysis

| Metric | Fast Food Meal (Burger/Fries) | Home Meal (Lentils/Rice/Veg) | Efficiency Note |

| Total Cost | $12.00 | $1.50 | Home meal is ~8x cheaper |

| Calories | 1,200 kcal | 600 kcal | Fast food is calorie-dense, nutrient-poor |

| Cost per 100 kcal | $1.00 | $0.25 | Home meal is 4x more efficient |

| Fiber (Satiety factor) | 4g (Low) | 15g (High) | Fiber prevents the “Sugar Crash” |

| Cost per gram of Protein | $0.40 | $0.10 | Beans are a cheaper protein source than beef |

| Duration of Satiety | 2-3 hours | 5-6 hours | High fiber keeps you full longer 14 |

References within text:.1

Works cited

- Global Dried Pinto Beans Price | Tridge, accessed November 29, 2025, https://dir.tridge.com/prices/dried-pinto-beans

- Global Rice Price | Tridge, accessed November 29, 2025, https://dir.tridge.com/prices/rice

- The Price of a Big Mac Around the World – Voronoi, accessed November 29, 2025, https://www.voronoiapp.com/money/The-Price-of-a-Big-Mac-Around-the-World–1663

- Big Mac Index by Country 2025 – Data Pandas, accessed November 29, 2025, https://www.datapandas.org/ranking/big-mac-index-by-country

- Cooking at Home vs. Eating Out. What’s Better? | Journey Foods Blog – The Pie, accessed November 29, 2025, https://www.journeyfoods.io/blog/cooking-at-home-vs-eating-out-whats-better

- Saving Money in 2025: More Home Cooked Meals! – Plan to Eat, accessed November 29, 2025, https://www.plantoeat.com/blog/2025/01/saving-money-in-2025-more-home-cooked-meals/

- Counting the beans – UN World Food Programme, accessed November 29, 2025, https://cdn.wfp.org/2018/plate-of-food/

- New WFP report shows access to food grossly unequal as coronavirus adds to challenges, accessed November 29, 2025, https://www.wfp.org/news/new-wfp-report-shows-access-food-grossly-unequal-coronavirus-adds-challenges

- Is fast food really cheaper than rice and dried beans? : r/AskAnAmerican – Reddit, accessed November 29, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/AskAnAmerican/comments/fyvmul/is_fast_food_really_cheaper_than_rice_and_dried/

- How much does an average home cooked meal per person cost you vs. eating takeout (not sit down restaurants) – Reddit, accessed November 29, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/budgetfood/comments/13tn7wi/how_much_does_an_average_home_cooked_meal_per/

- Your Brain and Diabetes – CDC, accessed November 29, 2025, https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/diabetes-complications/effects-of-diabetes-brain.html

- Sugar and the Brain | Harvard Medical School, accessed November 29, 2025, https://hms.harvard.edu/news-events/publications-archive/brain/sugar-brain

- Fast food effects: Short-term, long-term, physical, mental, and more – Medical News Today, accessed November 29, 2025, https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/324847

- Role of Dietary Carbohydrates in Cognitive Function: A Review – PMC – NIH, accessed November 29, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12209867/

- The Afternoon Slump: New Study Reveals Impact on Workplace Productivity, accessed November 29, 2025, https://alertprogram.com/workplace-productivity/

- Poor employee health means slacking on the job, business losses, accessed November 29, 2025, https://ph.byu.edu/poor-employee-health-means-slacking-on-the-job-business-losses

- Poor workplace nutrition hits workers’ health and productivity, says new ILO report, accessed November 29, 2025, https://www.ilo.org/resource/news/poor-workplace-nutrition-hits-workers-health-and-productivity-says-new-ilo

- Impact of Obesity on Employment and Wages among Young Adults: Observational Study with Panel Data – PMC – NIH, accessed November 29, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6338917/

- Re-examining the Link between Obesity and Wages | St. Louis Fed, accessed November 29, 2025, https://www.stlouisfed.org/publications/regional-economist/october-2011/worth-your-weight-reexamining-the-link-between-obesity-and-wages

- Economic Costs of Diabetes in the U.S. in 2022 – PubMed, accessed November 29, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37909353/

- Economic Costs of Diabetes in the U.S. in 2022, accessed November 29, 2025, https://diabetesjournals.org/care/article/47/1/26/153797/Economic-Costs-of-Diabetes-in-the-U-S-in-2022

- Direct medical costs of obesity in the United States and the most populous states – PMC, accessed November 29, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10394178/

- Costs of obesity, obesity-related complications, and weight loss in the United States: A systematic literature review – NIH, accessed November 29, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12398626/

- How Much Does Obesity Cost the U.S?, accessed November 29, 2025, https://obesitymedicine.org/blog/health-economic-impact-of-obesity/

- Ultra-processed foods A global threat to public health, accessed November 29, 2025, https://www.globalfoodresearchprogram.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/GFRP_FactSheet_UltraProcessedFoods_2023_11.pdf

- The Hidden Dangers of Fast and Processed Food – PMC – NIH, accessed November 29, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6146358/

- Obesity and overweight – World Health Organization (WHO), accessed November 29, 2025, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight

- Economic impacts of overweight and obesity: current and future estimates for eight countries, accessed November 29, 2025, https://gh.bmj.com/content/6/10/e006351

- Publication: Obesity: Health and Economic Consequences of an Impending Global Challenge – Open Knowledge Repository, accessed November 29, 2025, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/entities/publication/515fa95f-0b6d-599c-b315-a997fd33eb3a

- Productivity loss associated with the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages in Mexico, accessed November 29, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30144486/

- Healthy Food Prices Increased More Than the Prices of Unhealthy Options during the COVID-19 Pandemic and Concurrent Challenges to the Food System – PubMed Central, accessed November 29, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9967271/

- How Food Affects Productivity: Science-Based Guide 2025 – Nutrition and Dietetics, accessed November 29, 2025, https://www.nutritioned.org/food-effects-productivity/

- Assessing the Impact of Workforce Nutrition Programmes on Nutrition, Health and Business Outcomes: A Review of the Global Evidence and Future Research Agenda – NIH, accessed November 29, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10178561/